You know that moment…the wail of “That’s not fair!” echoes across the kitchen, classroom, or car ride, and your knee-jerk response kicks in:

“Well, life’s not fair.”

“Get over it.”

“Too bad.”

It slips out, even if we don’t totally mean it. I get it — I’ve said it, too. Sometimes it feels like the only option when you’ve explained your decision for the third time or you’re trying to keep seventeen things from falling apart at once.

But here’s the thing:

Fairness matters to kids.

And when they say “That’s not fair,” they’re not just whining — they’re practicing moral reasoning.

They’re testing boundaries.

They’re scanning for justice.

They’re asking, in their own way: “Does what I say matter to you?”

What’s Really Behind “That’s Not Fair”

When kids say something’s unfair, they might be:

Noticing inconsistency in how rules are applied

Comparing themselves to a sibling or peer

Feeling left out or overlooked

Testing whether their voice carries any weight

But it’s more than a reaction — it’s a form of inquiry.

They’re figuring out how the world works.

Why did she get that and I didn’t?

Why are the rules different for them?

Does anyone see what I see?

They’re observing patterns, drawing conclusions, and finding the edges of logic, emotion, and power. They’re developing their inner compass — and learning how to use their voice.

And isn’t that what we want?

We want kids to recognize injustice.

To speak up when something feels wrong — whether in the classroom, on the playground, or out in the world.

When we take their concerns seriously, we’re not just resolving a moment.

We’re nurturing critical thinking, moral development, and agency.

That’s big work. And it starts with the small stuff.

A Recent Moment From My Classroom

I teach fourth grade — which, if you’ve spent time with nine- and ten-year-olds, you know is the golden age of fairness obsession. They are constantly watching to see if things are just, if rules are consistent, if voices are heard.

I teach at a public Waldorf school, and our curriculum meets kids exactly where they are developmentally. Fourth grade is full of stories and lessons that reflect this moral awakening. We study Norse mythology, where gods and giants wrestle with power and fate. We examine the balance of ecosystems in our animal studies. We explore measurement and fractions — all ways of weighing, comparing, and learning to discern.

So it’s no surprise that we’ve had hundreds of conversations about fairness this year.

Here’s one that stuck with me:

In our class, we have a daily “butterfly child” — a kind of student-of-the-day who gets to help with special jobs, lead the line, and enjoy small privileges that feel huge when you’re nine. All year long, we rotate through the list. But near the end of the year, once everyone’s had a turn, I start pulling names at random to fill the final days.

One morning, I pulled a name, and a student immediately said, “Wait! That’s not fair — she already got to be butterfly. I haven’t had a turn yet!”

He wasn’t mad. He wasn’t being dramatic. He was paying attention. And he was right.

I’d forgotten to remove her name after her previous turn. In the chaos of year-end transitions, it was an honest mistake — but to him, it felt like a breach of justice.

So I said, “You’re right. Thanks for speaking up. Let’s fix it.”

So we did.

He didn’t need a long explanation. He didn’t even need to be butterfly that day.

He just needed to know he’d been seen, and that fairness still mattered.

These are the moments when kids learn to notice injustice, speak up with courage, and trust that their voice makes a difference.

What to Say Instead

Here are a few go-to phrases I use when fairness flares up:

“It sounds like this doesn’t feel fair to you. Want to tell me more?”

“I hear you. What do you think would feel more fair?”

“Sometimes things look equal on the outside, but are still fair in different ways. Want me to explain?”

“Thanks for noticing that. Want to help me think through a better solution?”

They’re not magic words, and they won’t erase every disappointment.

But they signal: Your perspective matters. I’m listening.

That alone makes a difference.

Fair Doesn’t Mean Equal (And That’s Not a Bad Thing)

One of the hardest — and most essential — concepts I teach is this:

Fair doesn’t always mean equal.

By fourth grade, kids are deeply aware of differences — who gets what, who gets support, who has accommodations. And it can feel confusing, especially when someone else appears to be getting something “extra.”

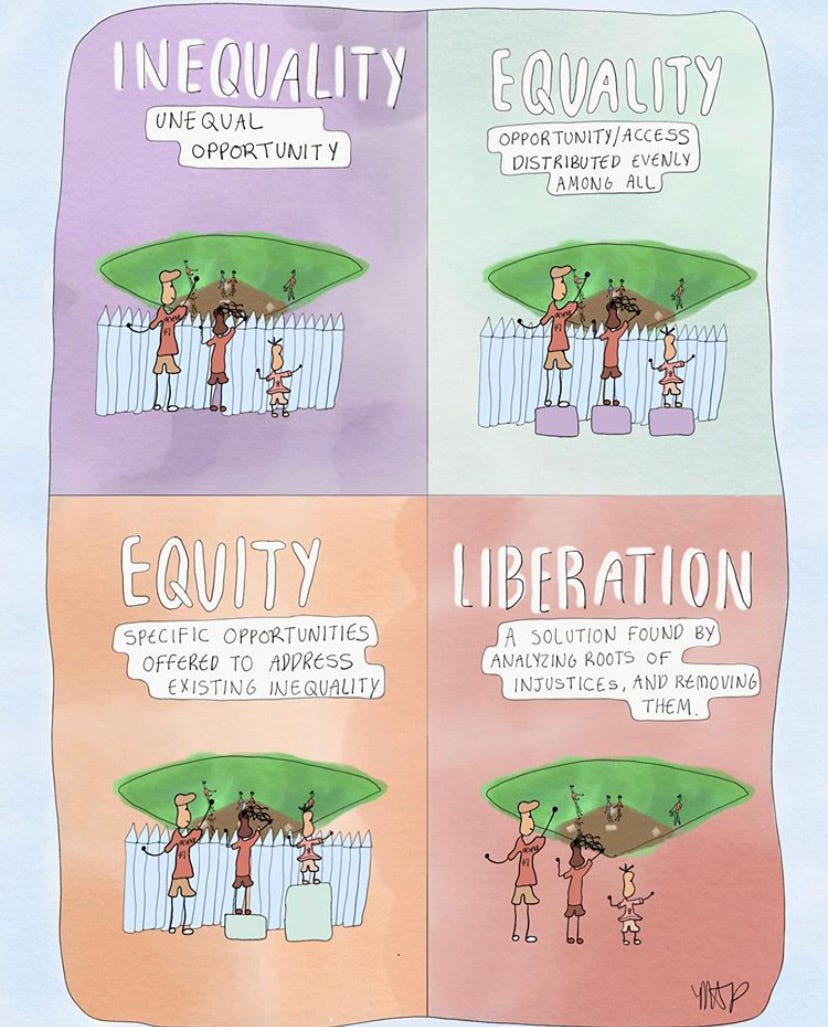

So I use a version of the classic visual you may have seen:

Four children watching a baseball game over a fence (the clearest and cutest visual I’ve seen to explain these concepts to kids…and drawn by my baby sister!)

Inequality: One child can’t see at all.

Equality: Everyone gets the same-sized box — but some still can’t see.

Equity: Each child gets the right support to see the game.

Liberation: The fence is gone altogether.

When I show this, I ask my students:

“If someone breaks their leg, do we all start using crutches just to be fair?”

Fair isn’t about giving everyone the same thing. It’s about giving each person what they need to thrive.

Why It Matters

These conversations are especially important for the kids who are beginning to notice that not everyone’s path looks the same — and for the kids who are walking those different paths.

Instead of shutting those questions down, I lean in:

“You’re noticing something real — and asking the right question. Let’s talk about it.”

Because when kids understand the difference between equality and equity, they become less resentful and more empathetic.

They start to see that we all carry different loads.

That supporting each other doesn’t mean we’re not all capable — it just means we’re human.

And if they can learn that now, then maybe someday they won’t just be passing out boxes…

They’ll be the ones taking down fences.